February 18, 2026

February 18, 2026Introducing Chief: Delightfully Simple Agentic Loops

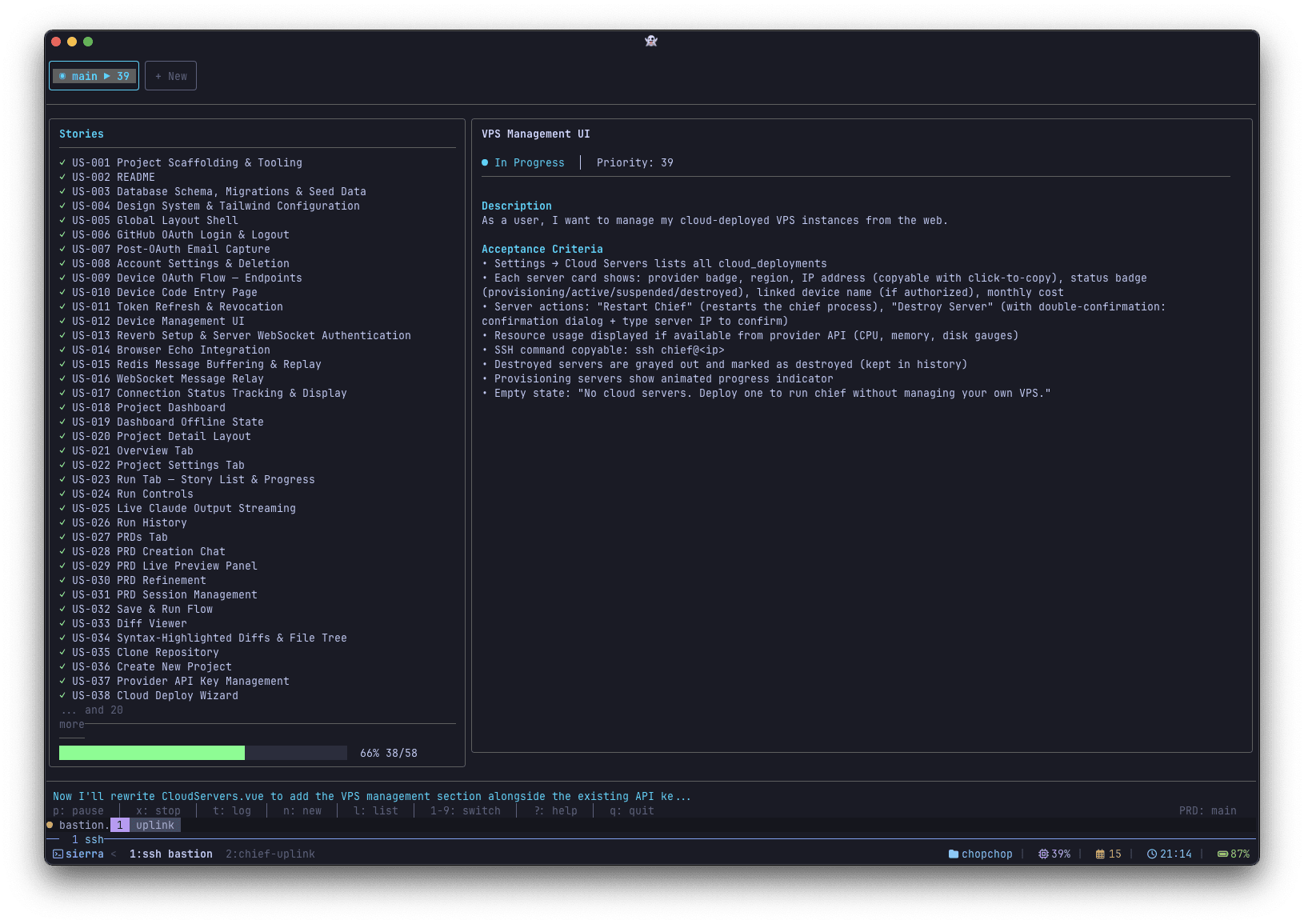

Chief is an autonomous coding agent that breaks projects into tasks and runs Claude Code in a loop to complete them one by one. It produces one commit per task, which makes reviewing the output much easier.

I'm giving a version of this as a talk at the Odense Laravel Meetup on February 25th, and hopefully as an attendee talk at Laracon EU. This post expands on those ideas.

Last month I wrote about Ralph Loops, wrapping Claude Code in a while loop with external state to build features while you sleep. At the end of that post, I teased that I was building a TUI called Chief to make the whole process easier. It's out now.

People are already using it to build things I didn't expect. Someone went from concept to a fully coded app in a few hours. Another person built an app they'd been dreaming about for years to manage their sports team league, but never had the time or capacity to build. Now it's real. Someone used it to build 13 competitor comparison pages for a marketing site. And yes, I used Chief to improve Chief itself.

But the interesting part isn't the tool. It's what I've learned about why some loops nail it and others don't. The answer, almost every time, is the spec.

How It Works

Chief was heavily inspired by snarktank/ralph, which I mentioned in the previous post, but with a focus on making the entire workflow more accessible. It handles spec creation, task breakdown, loop execution, and progress tracking, all from a single interface.

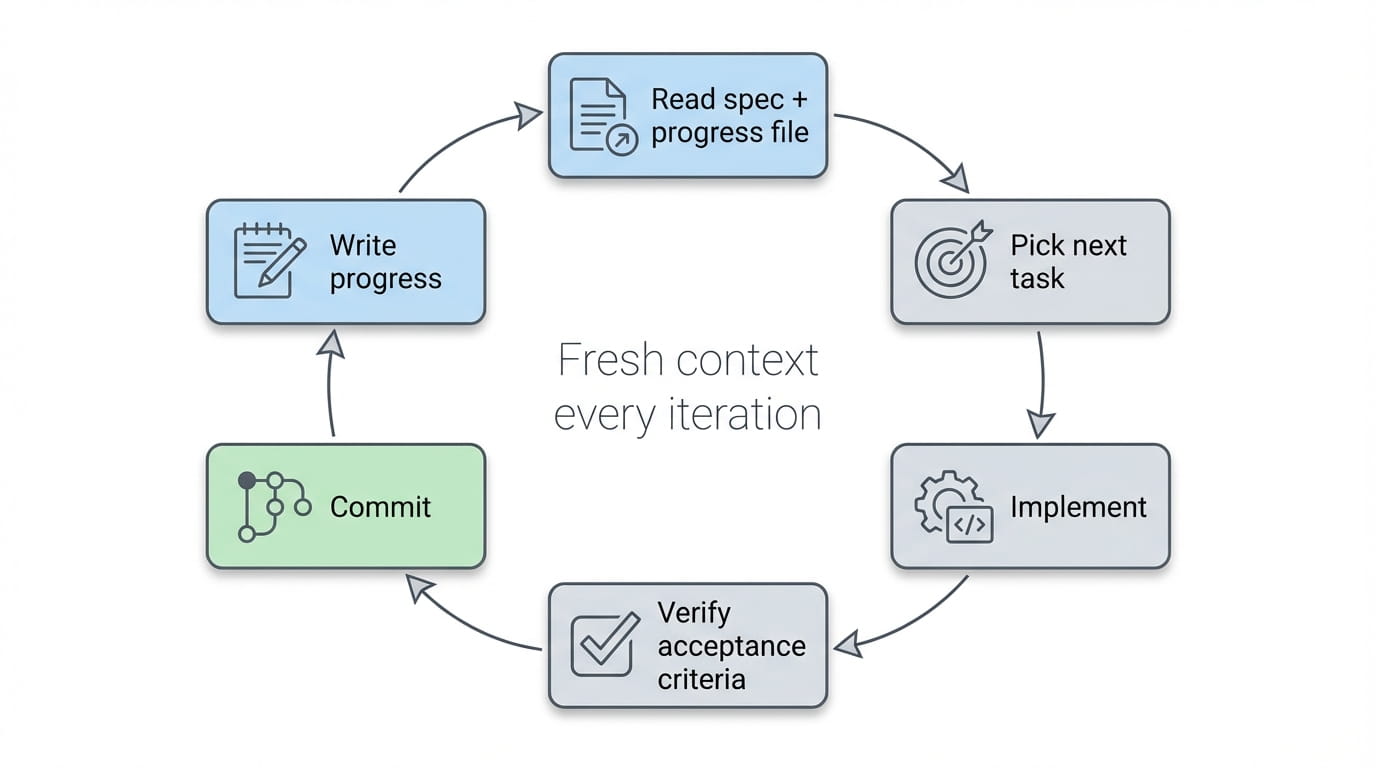

Everything lives on disk. This is the foundation that makes everything else possible. The spec, the task breakdown, the progress log, all of it is just files in your project. Each iteration starts with a fresh context window, reads those files to understand what's been done and what's next, does its work, and writes its progress back to disk. The AI doesn't need to remember anything because the state is external. That's how you avoid the context exhaustion problem that kills long sessions.

The progress file is shared context. Every iteration appends what it did, what it learned, and what tripped it up. The next iteration reads all of that before starting. It's how iteration 5 knows what iteration 3 figured out, without any of them sharing a context window. The "Learnings for future iterations" section is particularly valuable. More on that later.

Full transparency. When Chief creates a spec or breaks it into tasks, the prompts are right there in the Claude CLI. Nothing is hidden. You can see exactly what Chief is feeding to Claude at every step. If you don't like how a prompt is worded, you can see it and adjust your approach.

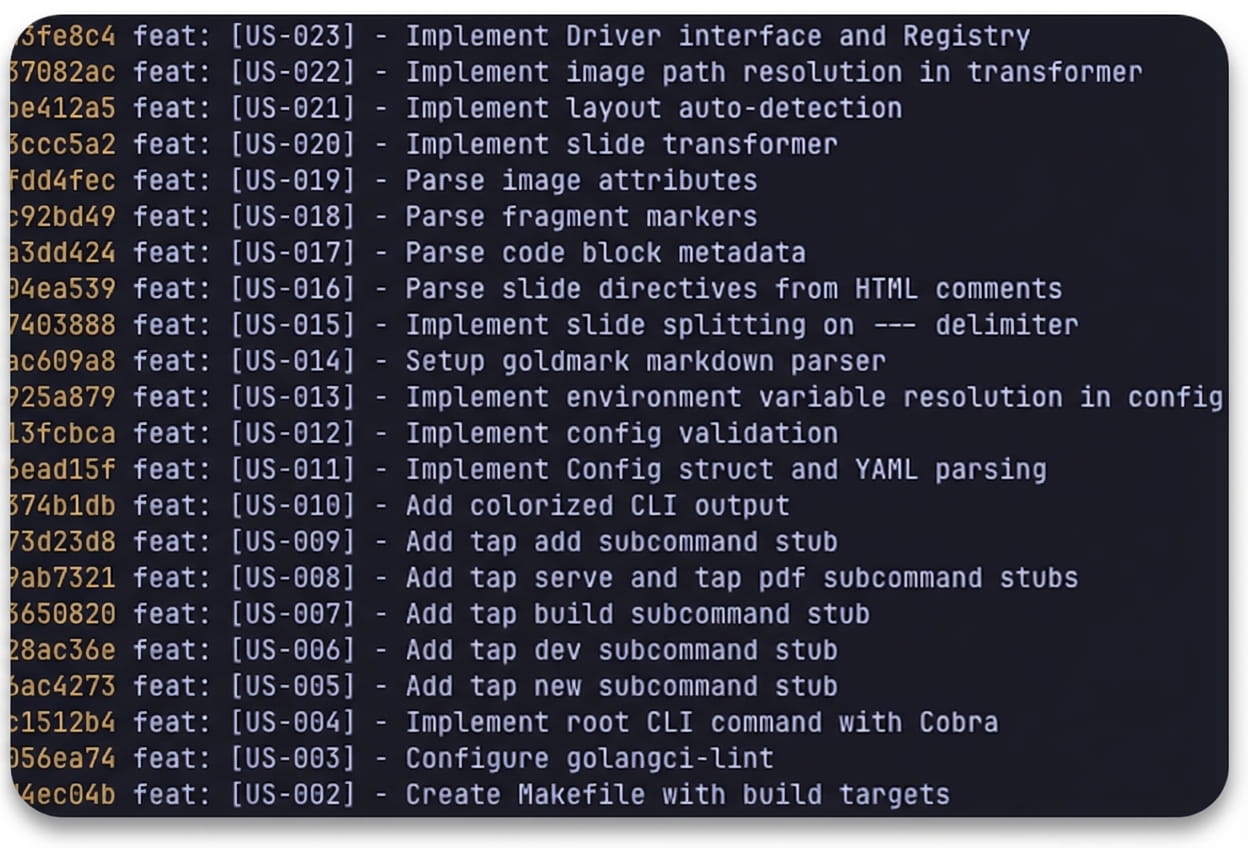

Commit-per-task. Each completed task gets its own atomic commit. This matters more than it might sound. Most loop wrappers accumulate changes until the context window degrades and the agent starts hallucinating. Chief's clean breakpoints keep each iteration fresh. It also means you can git log and see exactly what happened, or roll back a single task without losing everything else.

Resumable. Stop the loop, go to bed, pick it up in the morning. Since all state lives on disk, Chief just reads the spec and progress file to figure out where it left off.

Zooming Out

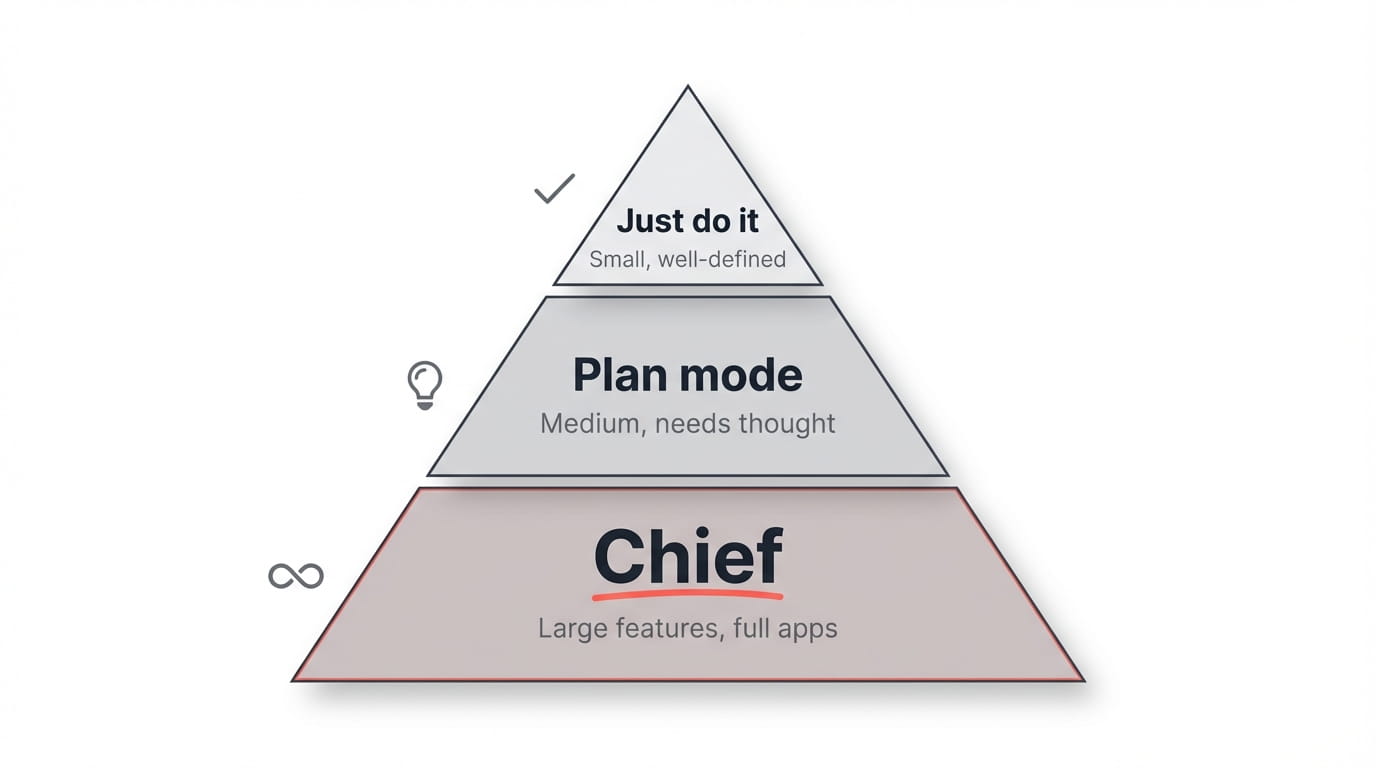

Chief is not a swiss army knife for all your AI coding needs. It's not going to replace Claude Code, Cursor, Copilot, or whatever existing workflow you already have. Those tools are great at what they do. Chief fills a specific gap that they don't cover well. Here's how I think about it:

Just do it. Small, well-defined tasks. Fix a bug, add a field, update some copy. You prompt Claude Code and it handles it. No planning needed.

Plan mode. Medium tasks that need some thought. A new feature, a refactor, something that touches multiple files. You use Claude Code's plan mode to think through the approach first, then implement.

Chief. Large features, full apps, entire project surfaces. The kind of work that would exhaust your context window long before you're done. You write a spec, break it into tasks, and let the loop run while you do something else.

Each step up means you spend less time on implementation and more time on specification. That tradeoff is the whole game.

Perfecting the Spec

Here's the most important thing I've learned: the spec is the product now.

Every vague sentence in your spec costs you a wasted iteration. Every missing detail costs you a bad commit you'll have to roll back. The quality of what comes out is directly proportional to the quality of what you put in.

If you've been writing specs your whole career, you already have the most important skill for this workflow. If you haven't, this is a great reason to start.

Think of Everything Upfront

When you're building a greenfield project with Chief, you're not just speccing features. You're speccing the entire project surface. This includes things you might normally leave for later:

Design and branding. For bigger projects, I spend time with Claude creating design guidelines, branding direction, and HTML mockups before I start the loop. Get the visual direction right first. Include color palettes, typography, component styles, whatever it takes to make the generated UI match what's in your head. This step alone dramatically improves the quality of the output.

Testing strategy. Browser tests with Playwright have been a game-changer for acceptance criteria. "User can see the priority dropdown on the create page" becomes a verifiable assertion, not a hope. I use Playwright tests heavily and combine them with PHPStan and PHPUnit for a solid verification layer. The more specific your acceptance criteria, the better the loop performs.

CI/CD. Have Chief set up GitHub Actions to run tests on commit. It's just another task in the spec. There's no reason not to include it.

Docs and landing pages. These aren't afterthoughts. They're spec tasks like everything else. When I built tap.sh, Chief built out the entire documentation website with examples, screenshots, and guides as part of the same run that built the app itself. I still had to read through everything and QA it, but it was 90% there. If your project needs a README, a landing page, or API docs, put them in the spec and let the loop handle them alongside the code.

Good Acceptance Criteria, Revisited

I covered this in the Ralph Loops post, but I keep coming back to it because it's the single biggest factor in whether a loop succeeds or fails.

The best acceptance criteria are commands Claude can run and specific assertions it can verify.

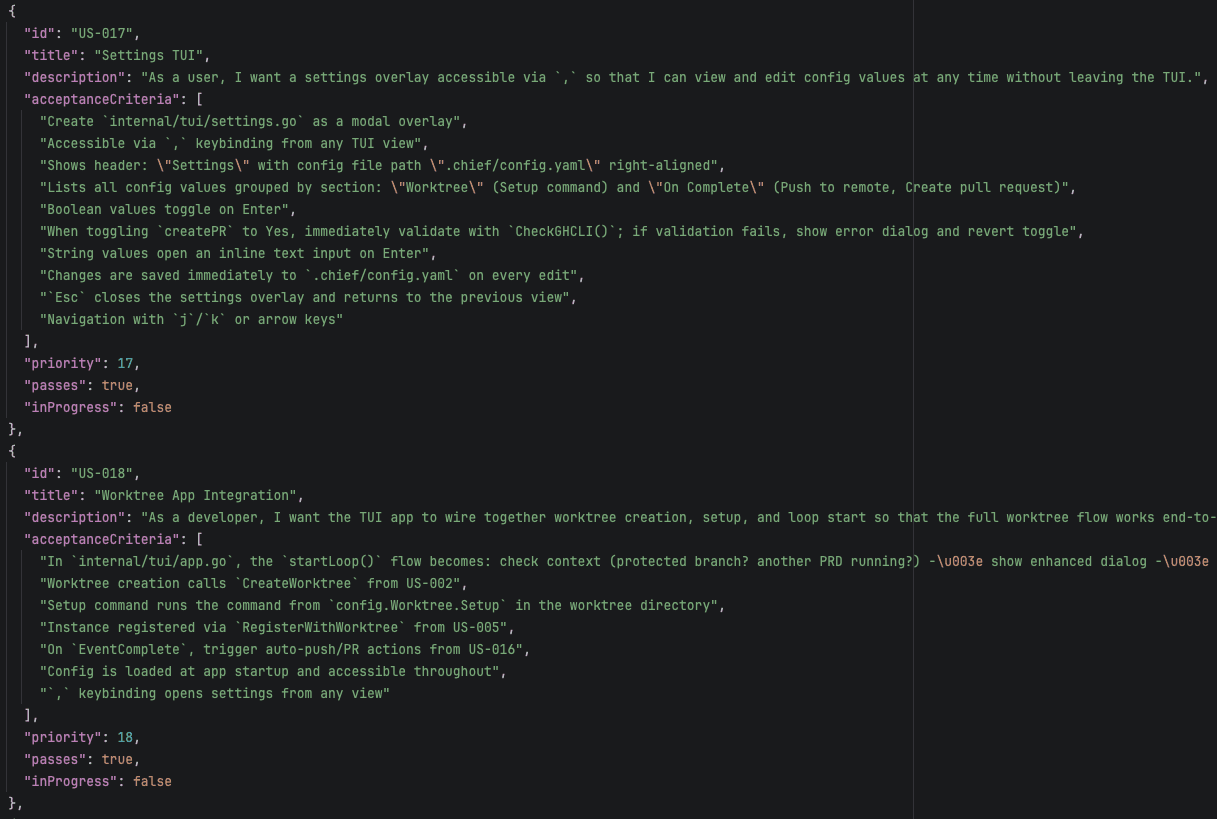

At a minimum, every task should include criteria like "test suite passes" and "linter checks pass." But the really effective criteria are the ones that describe exactly what the code should do. Here are some real examples from Chief's own spec:

- Config is loaded from

.chief/config.yamlon startup - If the config file doesn't exist, return a config with

push: falseandcreatePR: falseas defaults (no error) - If a worktree already exists for this branch, reuse it instead of erroring

- The confirmation dialog shows the exact paths being removed so the user knows what they're deleting

- After a PR is created, show the PR number, title, and a clickable URL

- Errors on the completion screen don't block the UI. The user can still navigate and use keybindings.

Notice how specific these are. Each one describes a concrete, verifiable behavior. Claude can check whether the function exists, whether it returns the right thing, whether the UI shows the right content. There's no ambiguity.

Chief handles writing acceptance criteria for you as part of the task breakdown step. But you can always review and nudge them in the right direction before starting the loop. If you notice vague criteria, tighten them up. That five minutes of review pays for itself many times over.

The weakest acceptance criteria are subjective statements like "feature works correctly" or "code is clean." Claude can't objectively evaluate those, so it'll mark them as passing and move on whether they actually are or not.

For web applications, Playwright tests are the strongest acceptance criteria you can write. They verify actual user-facing behavior, not just that code compiles. If you're building anything with a UI, include browser tests in your specs.

Editing the Spec Mid-Loop

One thing that surprises people: you can edit the spec after the loop has already started.

Stop the loop, edit the spec, restart. This works because each task in the spec has a simple "passes": true/false flag that tracks completion. Chief picks up where it left off by finding the next task that hasn't passed yet. Since each task also gets its own commit, you have natural rollback points in git if things go sideways after an edit.

This is particularly useful when you realize partway through that you specified something wrong. Maybe the first five tasks are great but the sixth is headed in the wrong direction. Stop the loop, fix the spec, and let it continue. You can even git revert the bad commits and re-run those tasks with the updated spec.

Multi-Project Specs

For projects that span multiple repos (say, a CLI tool that connects to an API backend), I've found a workflow that works well.

Start by writing up an overall description of what you're building. Pull up your favorite LLM chat (I use Claude Desktop for this) and hash out the full picture: what each piece does, how they communicate, what the interfaces look like. This isn't a spec yet, just a shared understanding of the system.

Then fire up Chief twice, once in each repo, and let it create separate specs for each project. Feed it the overall description as context so both specs stay aligned on interfaces and contracts.

Run them independently. Each repo gets its own loop. You can even run a Chief loop first that builds out something like an OpenAPI spec, and then have both apps consume that as their source of truth.

I did this recently with a CLI tool that communicates with a WebSocket backend written in Laravel. I started by describing the full system in Claude Desktop: the message format, the WebSocket events, the authentication flow, how the CLI would connect and exchange data. Once the overall picture was clear, I fired up Chief in both repos and fed each the same system description. Both specs stayed aligned on the wire protocol because they were working from the same source document. The two loops ran in parallel, and because the contract was defined upfront, the CLI and backend connected on the first try.

Read Your Progress File

This tip came from several people who've been using Chief, and it's a really good one.

After Chief runs through a bunch of tasks, go read the progress file. Specifically the "Learnings for future iterations" section. Each iteration writes down what it discovered about your project: patterns, conventions, gotchas, things that worked and things that didn't.

The loop is teaching itself about your codebase, and in the process, it might teach you something too.

I've found genuinely useful insights buried in progress files. Things about my own projects that I hadn't noticed or had forgotten about. It's worth the five minutes it takes to read through.

And when you find something good, pull it into your CLAUDE.md file so future sessions benefit from it too.

On Using This with Existing Codebases

In the Ralph Loops post, I said I'd be hesitant to use this on a large established codebase. There's too much implicit knowledge, too many conventions, too much risk.

I've changed my mind. Partially.

It is possible and sane to use Chief on existing codebases. But there are prerequisites, and they're non-negotiable:

Good existing test coverage. The loop needs to verify that it's not breaking things. If your test suite is thin, the loop will happily introduce regressions without knowing it. Comprehensive tests are the safety net that makes this work.

Modular design. If your codebase is a tightly coupled monolith where touching one thing breaks five other things, the loop will struggle. Modular, well-separated code gives the loop room to work on one piece without accidentally destroying another.

And code review is more important than ever. Chief can produce a lot of code very quickly. That's a lot of surface area for bugs, security issues, and subtle mistakes. Don't just merge the branch because the tests pass. Read through the commits, understand what it did, and push back where needed. The loop handles implementation, but you're still the one responsible for what ships.

If your codebase has good test coverage and a modular architecture, go for it. Stick to well-defined, isolated features and you'll be fine.

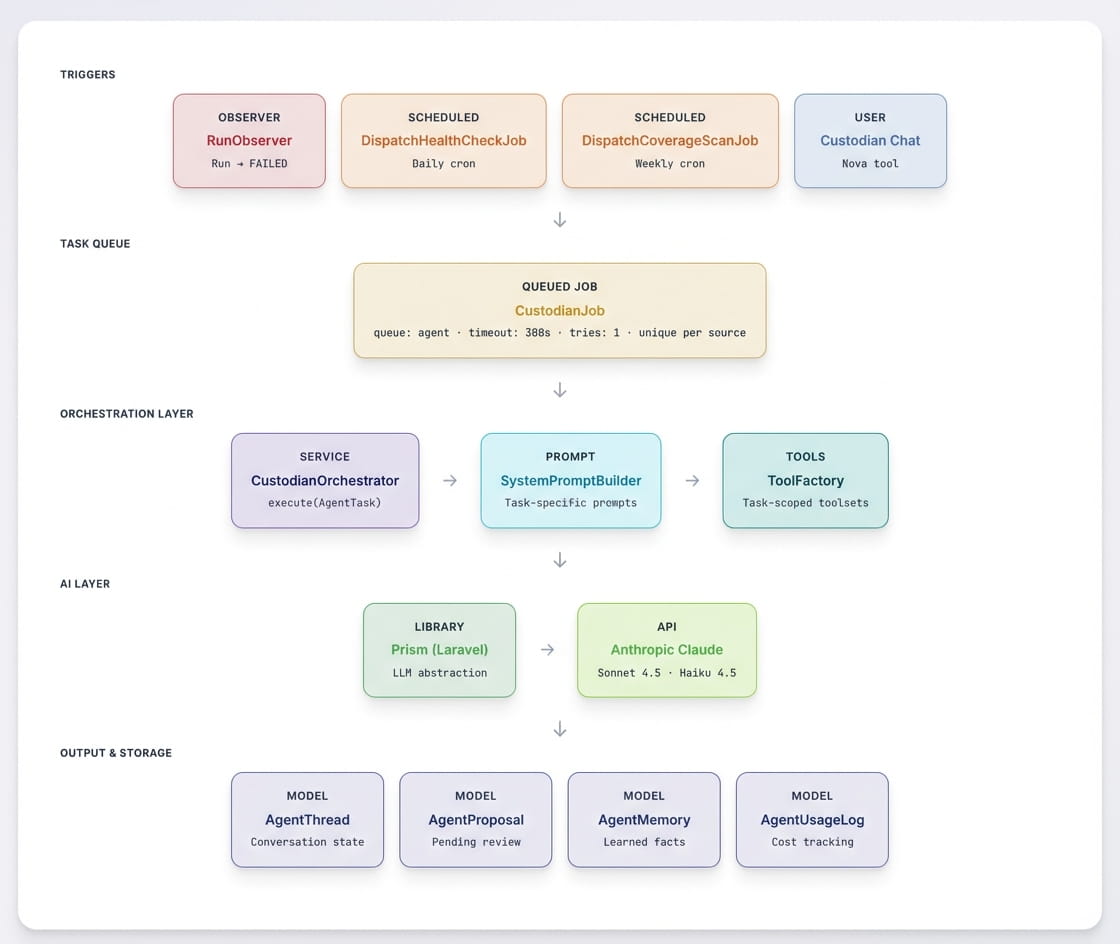

Case Study: Building Custodian

I recently put this to the test on a transatlantic flight. I used Chief to build what we call Custodian: an autonomous AI agent embedded in Geocodio's internal ETL platform. It's the most ambitious thing I've built with Chief so far, and it's a good example of what's possible when the spec is solid and the codebase is ready for it.

What it does. Geocodio ingests data from thousands of sources. Sources break. URLs change, schemas drift, fields get renamed. Before Custodian, someone on the team had to investigate every failure manually. Custodian handles that autonomously. It monitors data sources, investigates failures, proposes fixes with risk scores, and lets the team chat with it for on-demand investigations.

Three operating modes. Reactive mode triggers automatically when a source run fails, investigates root causes, proposes fixes, and can run test builds to verify them. Proactive mode runs on a schedule: health checks daily, coverage gap analysis weekly, enrichment scans monthly. And directed mode gives the team a chat interface to ask it to look into anything data-related on demand.

21 specialized tools. The spec defined 21 tools across four categories. Diagnostic tools for inspecting sources, reading run logs from ElasticSearch, diffing schemas against upstream changes, and checking URL endpoints. Research tools for web search, fetching pages, sampling GeoJSON data, and analyzing coverage gaps. Proposal tools for suggesting conform fixes, URL updates, new sources, and source retirements. And action tools for dispatching test builds, saving persistent memories across investigations, and escalating to a human when needed.

Everything goes through review. Custodian never modifies sources directly. Every change is a proposal with a risk classification (low, medium, or high) scored automatically based on the type and scope of the change. A single field mapping fix is low risk. Changing more than half the fields in a conform is high. New sources are always high. The team approves or rejects each proposal, and low-risk fixes can optionally auto-approve if a test build passes.

Built-in cost controls. The spec included per-task, daily, and weekly budget limits, all configurable. An 80% threshold alert fires before hitting the daily cap, and the job simply refuses to start if the budget is exceeded. Every API call is logged with token counts and estimated cost.

The output. Chief produced 22,000+ lines of code across the feature: the orchestration layer, all 21 tool implementations, 6 database migrations, real-time WebSocket broadcasting for the chat UI, a Nova frontend component, and the full configuration system. I reviewed every commit as it came in.

The codebase it was built into is large and established, but it has solid test coverage and a modular architecture. That's what made it possible. The spec was detailed, the acceptance criteria were specific, and Chief had room to work without stepping on existing functionality.

Models and Usage Limits

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: usage limits.

If you're serious about working with agentic loops, just go for the Claude Max 20x plan. Don't try to do this on the Pro plan. You'll hit limits within minutes and spend more time waiting than building. $200/month is table stakes if you're building real things with this. The real constraint is staying within the session and rate limits that come with the plan.

In my experience, two concurrent Chief runs on a 20x plan works fine. Three and you'll start bumping into session limits fast. Someone I know burned through 98% of their session tokens in about 20 minutes running three concurrent Opus tasks. The trick is to be deliberate about how many loops you're running at once.

One practical way to stretch your limits: Opus for creating specs, Sonnet for implementation. Spec creation is where you really need the smarts, but implementation with a solid spec doesn't need as much horsepower. Sonnet 4.6 is good, and using it for the loop runs will stretch your usage limits a lot further.

Where Chief Falls Short

Chief fails when the spec has gaps. If you haven't made the key technical decisions upfront (what library to use, how authentication works, what the data model looks like) the loop will make those decisions for you, and the results won't always be consistent. The progress file helps carry context forward, but it's not a substitute for actual decisions in the spec. You really need to spend that extra five minutes on the spec and make sure you've covered everything. Open questions in the spec produce inconsistent commits, and you'll burn iterations rolling them back.

It's also overkill for small projects. If your task fits in a single context window, just use Claude Code directly. Chief adds overhead (spec creation, task breakdown, the loop startup) that doesn't pay off unless the project is big enough to need it. Refer back to the three-tier model: Chief is for the top tier, not the bottom two.

Where This Is Heading

"SaaS is dead" is having a moment online. It's not. Getting a first version of something working is only the beginning. You still have to maintain it, handle the security updates, and keep iterating on it month after month as real users hit it in ways you didn't expect. That's the hard part, and it doesn't go away because an AI wrote the first draft. The gap between "I can describe what I want" and "I have a production-ready product I can rely on" is smaller than it used to be, but it's still very real.

What is changing is custom tooling.

High-performing developers and companies are going to build dramatically more internal tools that fit their specific workflows. That workflow that's "almost but not quite" served by an off-the-shelf SaaS? The cost to build exactly what you need just dropped off a cliff. And the cost to maintain it dropped with it, because you can point the loop at bug fixes and improvements the same way you pointed it at the initial build.

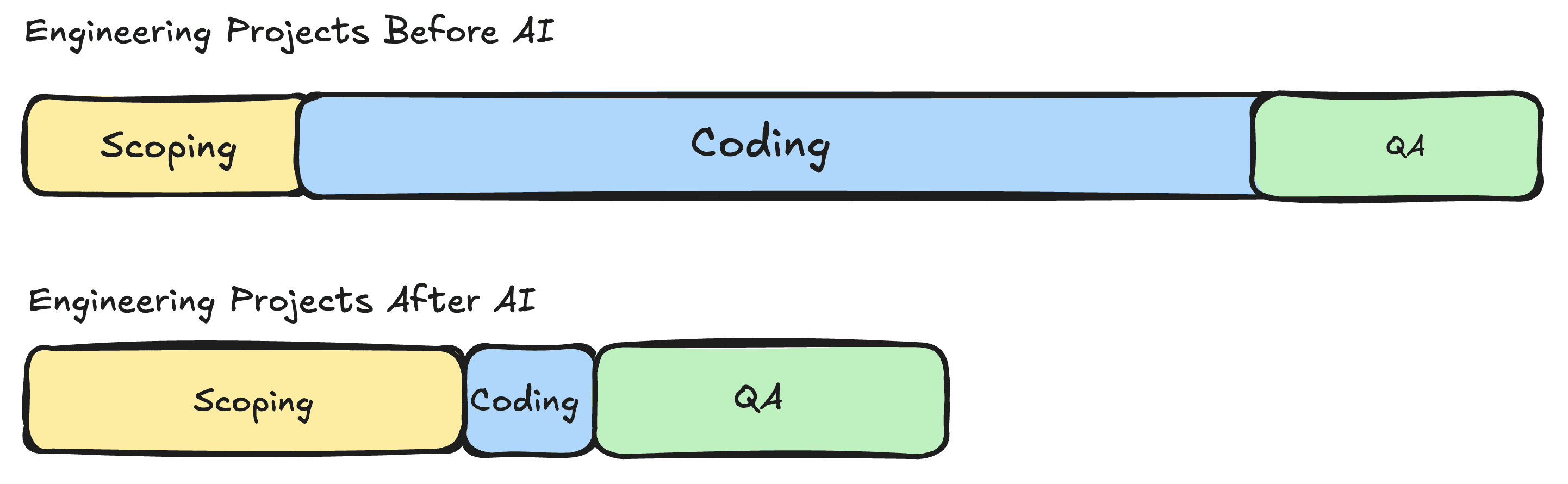

The developer experience workflow has never been better. The craft is shifting from implementation to specification. And the tools (Claude Code, Chief, whatever comes next) are shifting with it.

Michele's illustration from her earlier post captures this perfectly. The time you spend on a project is redistributing. Implementation used to dominate. Now scoping and QA take up a larger share, and the implementation phase compresses dramatically.

Illustration by Michele Hansen

Illustration by Michele Hansen

Wrapping Up

When I wrote the Ralph Loops post a few weeks ago, I was still figuring this out. I'm still figuring it out, honestly. But the gap between "interesting experiment" and "this is how I build things" has closed a lot faster than I expected.

If you want to try Chief yourself: minicodemonkey.github.io/chief. And if you haven't read the Ralph Loops post that started all of this, start there.

Now if you'll excuse me, I have a talk to prepare. Chief's already on iteration 7.